C. (BB.) Spirit: VI. Spirit: C. Spirit that is certain of

itself. Morality (364-409)

Wednesday, 22 April 2015 (notes by Marton Ribary)

Only the movement is real:

Hegel’s dialectical method has demonstrated that whatever is

treated as stable will necessarily destabilise itself by having been contrasted

with its opposite. The dialectical movement of reflection allows no room for

the so-called “eternal truth” that philosophy has been chasing for too long. Inasmuch

as thought is treated as a single, solid and stable piece of knowledge, it

becomes immediately fragile to challenges. Only the movement is real, and

therefore only the constant progress from one form to another can hold the claim

to be true.

The reality of thoughts:

Consequently, contrary to the long-standing philosophical dogma,

inasmuch as a thought is true, it must be real, inasmuch it is real, it must be

moving and alive. They are not the eternal Platonic entities that mortal humans

occasionally take part of when they have reached an advanced level of

philosophical reflection. The age old contradistinction between mortal humans

and immortal thoughts is a mistake – mortals do not borrow immortal ideas when

they think. What I think here and now is not the same what Plato thought 2400

years ago. In short, there is no such thing as philosophia perennis (and

thereby a good part of contemporary analytic philosophy is following a

dead-end.) Just as humans are born, live and die, thoughts are living entities too.

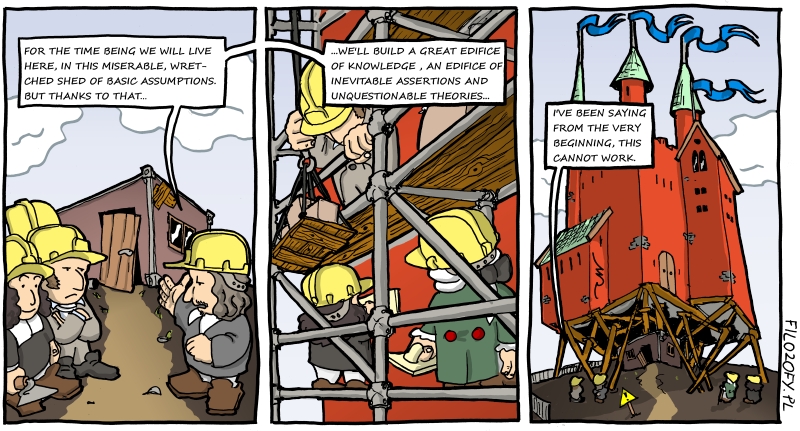

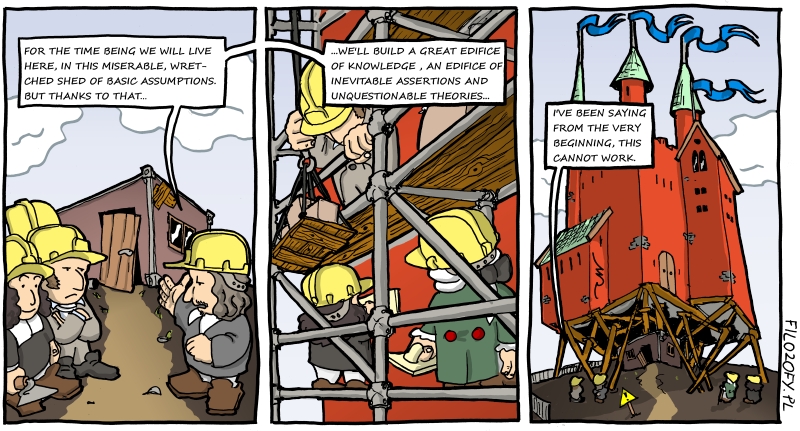

The empty nature of morality:

In the previous section, Hegel has demonstrated with strong

allusions to the French Revolution that absolute freedom is empty and eventually

devours itself. He moves on to discuss whether morality can be used as a

reference point for our conduct, and concludes that all externally set rules

are empty and meaningless. Set rules destabilise themselves because what is

treated as solid and unchanged falls victim to dialectical reflection. Moral standards

set by another consciousness (God, society, the perfect law-giver, Kant’s

formal rules etc.) turn out to be empty and meaningless, because they are dead

and do not move forward, and because they are outside the consciousness (the “I”)

who is supposed to follow them.

The acting conscience:

Internalised, dynamic and self-constituted standards seem to be

the solution for the problem of human conduct. In what Hegel calls “duty”,

conscience serves as the force of human action. Just as set standards turn into

their opposite by dialectical reflection, abstaining from action and thereby

creating a moral zero is similarly static and self-destroying. The “beautiful

soul’s” solution to the moral conundrum of action eventually leads nowhere. By

overcoming the self-destroying character of static standards of conduct, acting

conscience (that is, duty) is capable of moving towards self-realisation

without turning into its opposite and eliminating itself in the process. The key

is that self-realisation is not achieved by reaching a set target or by living

a perfectly moral life, but by being recognised by another consciousness. The

acting conscience realises itself by being recognised by another.

No comments:

Post a Comment