Descartes, Meditations

- Letter to the Sorbonne, Preface to the reader, Synopsis and the first two

meditations (pp. 1-34)

Wednesday, 28 September 2016

(notes by Caroline Kaye and Marton Ribary)

Page

numbers in Descartes refer to the marginal page numbers corresponding with the

first edition.

The goal of the

Meditations

The Letter to the Sorbonne claims that the Meditations

shall provide evidence for the existence of God and the immortality of the

soul. The goals Descartes announces here are extremely traditional, and they do

not correspond to what actually happens in the Meditations. Birsen Dönmez

(BD) pointed out that Descartes changed the title of the Meditations from

the first edition which expected to secure the endorsement of the Sorbonne. As Descartes

was unsuccessful in securing that, he must have felt that the scholastic disguise

was no longer necessary.

Skepticism

Alex Samely (AS) asked whether it could be a ruse to undermine

scepticism (itself). Can doubt in a measured way become a new anchor for

knowledge? Leif suggested that it was a tool for establishing certainty, the

acquisition of knowledge. Radical scepticism would make it impossible to

function as one would not be able to trust anything, not even the ground

beneath one’s feet. It was hotly debated whether the existence of the “I” was

sufficiently demonstrated, or it was merely postulated as part of Descartes’

radical thought experiment. What is a proof, what is a mere proposition when

radical scepticism gets rid of all assumptions which might be used for building

an argument?

Descartes denies certainty from anything in the world. His senses

can fool him, memory can lie. He needs to take everything back to a primordial

point of certainty. How do we know that the world is not illusory? Knowledge of

the world (if it exists!) comes via senses which are not reliable. “We must

reject what they seem to teach us”[1]

Meditation

The use of the word “meditation” is meant to signify “a process

of thought” as opposed to our more modern idea of clearing the mind of thought.

(It is actually quite difficult to be conscious of oneself not thinking.) In a sense Descartes is taking the reader on a

journey, and we are invited to “think along” with the meditator. The force of his

argument only works, if the reader plays along. The chosen method in Descartes reflects

the first person perspective of the project: the certainty of the “I” can only

be established for one’s self.

Descartes attempts to strip back what can be known in order to

establish a method of enquiry into knowing, effectively his own reconstruction

of knowledge.[2]

His eschewing of scholastic discourse makes the mediations more personal, and

is according to Charles Taylor, an example of “radical reflexivity” where one

“focuses not on the objects of one’s experience, but on oneself as experiencing

it.”[3]

The certainty of

the “I”

In the second meditation, Descartes tells his reader that he

recognises “for certain” that “there is no certainty”. (24) Leif Jerram (LJ) drew

our attention to a passage on p. 22 where Descartes says that: “So in future I

must withhold my assent from these former beliefs just as carefully as I would

from obvious falsehoods, if I want to discover any certainty”. A lively debate unfolded

around a paragraph on p. 25 paraphrased below.

I can be certain that I am thinking. This satisfies me that I

exist. I cannot be certain that you exist, or anything else for that matter.

But I can be sure that my thinking means that I exist. I am because I am a thinking thing. We do not at this point have

any definition of what this “thing” might be, or what the “I” actually consists

of. The important point is that even if I am a puppet who has had thoughts

inserted into it by a malevolent being (Not God), then this does not negate the

thought or the thinker as it were, rather it proves existence because thinking

is happening. I know I’m thinking, it is the only thing I am certain of.

We returned again and again to the concept of the “I”, or the

“self”. It was stressed that at this point Descartes had not declared a

position on what the “I” is at all. At this point, AS was keen to know whether

anyone in the group was convinced by Descartes’s claim. And if not, how would one

argue for it not being convincing? How would you demonstrate that

Descartes is wrong? There then ensued a lively debate about whether or not the

argument was convincing, or whether it was preferable to read on before making

a judgement. AS felt that it was important to get this clear as there were

implications around this for notions of being, what it means to “be”.

Marton Ribary (MR) and Bobby Silverman (BS) drew our attention to

a related passage on page 27 where Descartes states that “thought; this alone

is inseparable from me”. He further says that “And yet may it not perhaps be

the case that these very things which I am supposing to be nothing, because

they are unknown to me, are in reality identical with the ‘I’ of which I am

aware? I do not know, and for the moment I shall not argue the point, since I

can make judgements only about things which are known to me.”

The hidden temporal

aspect

Descartes introduces a

hidden temporal aspect when in the crucial passages on page 25 and 27 he says

that the postulated malignant demon “will never bring it about that I am

nothing so long as (quamdiu) I think that I am something” and that “I am,

I exist – that is certain. But for how long (quandiu). For as long as I

am thinking.” We may then ask whether certainty has a limitation, and it is only

established as long as I think. If so, how does this relate to Descartes’

claim that unlike the body, the soul is indissoluble and imperishable. He acknowledges

an intimate unity between the body and soul during one’s bodily existence, but

he yet claims that only the unity is temporary, but the existence of the soul predates

the body’s existence and it survives its dissolution.

Additional material: Philosopher Barry Smith on Descartes and Consciousness (BBC Radio 4, A History of Ideas, 17 April 2015)

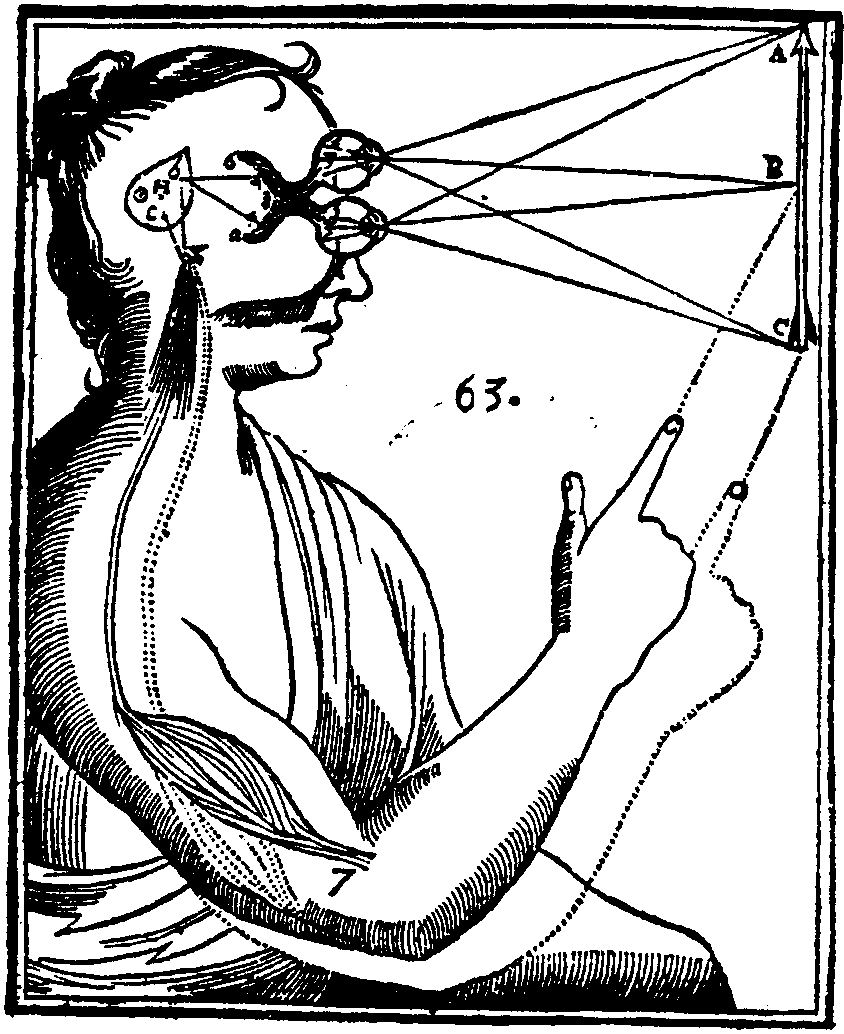

A diagram by Descartes in his optical treatise